Enthusiastic, ready to jump in, ready to start to teach drawing, but knowing nothing about it other than experiences as a student. Having been drawing “forever”, and always encouraged as a child to draw, any instruction was welcomed.

The "rules" of drawing, that one must observe and draw from "life" got in the way. If anything visually appealing was traced and copied before long there was no problem drawing that particular subject from life or even memory. There was always something that couldn't be drawn - but there was so much interesting material that it was easy to ignore what was beyond any current ability. If some new subject appealed, there were always drawings or photos to trace and use the tracing process to master the form.

Drawing classes in high school and university were conquered by being obsessive and dogged rather than because of any talent or innate ability. As the experience of teaching grew over time, a realization grew that the major influence on improving drawing ability was the time one was willing to put into it, to keep at it, to develop a drawing habit, to practice.

Many people have expressed a desire to know how to draw and my answer is learning how to draw is really easy: buy some tracing paper and begin tracing any image that they find interesting and that they'd like to be able to draw. Then comes the caution that that's the easy part; the hard part is continuing to do it again and again over time. If they are not willing or able to do that then they can have no hope of becoming accomplished at drawing.

Two things about that advice are usually questioned. The first is recommending that one learn to trace and copy and the second is that repeated practice is required. In reverse order, practice is the easiest to explain. A student in a drawing class, whether in high school or college, has a built in stimulus to practice: their grade, the regular scheduling of classes and the practice required to accomplish a decent grade.

The nature of drawing classes tends to disguise this scheduled practice with an overview, a variety of exercises, that stimulate awareness of the different skills needed to see and draw well. But the heart of the drawing class is the enforced practice. Without it there is no progress and little learning.

Drawing is like any other physical skill. It involves the acquired acquired ability to coordinate one's eyes, hands and mind. Learning music requires more since the ear must be included in the equation. How to get to the Met? Practice, practice, practice. The willingness to practice is the most important aspect of learning any skill and especially the skill of drawing. A few of my students did not hesitate to tell me that my class was a failure and that they'd not been taught anything about drawing. The reality for those students was that they never had the experience of learning a physical skill of any kind and never practiced. They were taught about drawing but were on their own when it came to practicing, failing, seeing, succeeding and pushing their pens; they wanted the ability without the work. It was easy to tell them they were my most disappointing students and why. Their experience might be compared that of a student who “learned" a language but couldn't speak it or understand a native speaker.

The more controversial aspect of this approach to learning to draw quickly and effectively is tracing and copying. A few years after beginning teaching, at a gathering hosted by an architectural graduate of our school, our conversation turned to how things were going at his alma mater. He'd heard that the drawing classes had gone down the drain since whoever was teaching there now had students tracing projected slide images and working with grids and other ways of "cheating". When it was pointed out that copying and such tracing techniques were part and parcel of the teaching and practice of drawing by masters at least since the Renaissance, his attitude began to evaporate as he tried to come up with valid contradictions. He was also a bit surprised when told he was speaking with the culprit.

The process of tracing, with tracing paper over an image, tracing a projected image or even transferring an image via a grid from one surface to another links the eye and the hand in a way that trains both so that they can work together. With practice, the eye and hand become adept at following the contours of the traced image. If the image is of the real world, the eye begins to be able to transfer the experience to seeing the contours of the real world that might become a drawing. At first, the mind is occupied in telling the hand what to follow and is critical of the effort. As practice progresses, the mind can relax and let the hand and eye do their work and can then impart the spirit, introduce the new ideas that come while watching the process as it proceeds and improves.

The hand develops the physical skill of delineating, making an image, on a two dimensional surface. Practice trains the hand to respond to the eye and make the movements necessary to put down what the eye sees in the image being traced.

We go through life assuming that what we see appears exactly the same to the person we're standing next to. Teaching drawing with such a plainly understood process as tracing exposes the fallacy of that belief. Different students who copy the same subject often produce images that are quite different except in their overall layout. The surprising thing about this is that it exposes the fact that we all see differently. Mostly, the differences are very minor but some students were constantly frustrated by the idea that their drawings looked nothing like what they thought a "good" drawing should look like. What they produced looked too different from what they saw in books about drawing, in museums or just what other students in their class were producing.

They were looking in the wrong book or the wrong part of the museum. Their own way of seeing was alien to an ideal of drawing they'd come to accept. Personally, there was no way of grasping this until a conversation with a friend who said that she had never understood the art of Picasso and that it bothered her. Then she had an experience with a drug that changed her own perception so that it enabled her to see the world as Picasso might have seen it. Picasso's work became a newly rich experience since she now saw it not only as a new but another way of seeing. Occasionally, as students who were directed toward work that resembled their own way of seeing, their frustrations began to diminish.

Artists like Dürer and his contemporaries were fascinated with copying techniques like the camera obscura, grids and tracings. Artists have always used any technique they could find to improve their drawing and to help them to delineate accurately. Today we have photography and Dürer would have loved it. Using tools that make the recording of an image easier and more accurate is basically not much different than the use of a wrench to remove or tighten nuts and bolts.

Albrecht Dürer - Artist Drawing a Nude

The advent of the camera and the use of photography in art has been exploited in the work of the "photorealists". Their work which has been exhibited in the mainstream is concerned by and large with photographic accuracy at the expense of content beyond the physicality of the rendered scene.

Relative to drawing and painting, an aspect of the use of the camera that has been neglected is the camera's ability to "stop" time. An artist painting a scene from life is confronted with constantly changing light and movement. Laying in the details of an image might take place on a day that's radically different from the day on which composition was first blocked in. If the painting requires a long time to complete, even seasonal changes can affect the character of the scene.The camera allows the artist to establish a base in time and to further record changes seen in the scene as the painting or drawing progresses. The camera also allows the artist to freeze movement in a scene with an accuracy difficult to achieve even through very careful observation.

Working in a space that overlooked the East River in New York, drawn again and again to the view of passing ships filling the windows, the changing light, the movement of the water and the reflections upon it were irresistible. A camera on the job became a necessity and when something passed that was striking, a snapshot saved it. Sometimes the light in the workspace would flicker; the light of the sun reflected from the water, flaring and pulsed there. Photos of the water on slide film, were taken, put away and forgotten.

Later, working on drawings based on a different series of photos, one of the "water” slides popped up. Projected and and traced, something magical appeared on the paper and then never lost its power to fascinate. Here was an instant rendered with ink, by hand, that captured a split second completely. Magritte said that the magic of a painting was simply that it had been painted. In the same way this drawing fascinated because it had been “drawn”.

East River

East River

There was another message the drawing had to deliver that only became apparent much later. The East River drawing was done accidentally in a way that made the edges of the image not parallel with the edges of the paper. Every now and then when the picture was seen out of the corner of one's eye, it had a three dimensional quality that was decipherable, defying explanation.

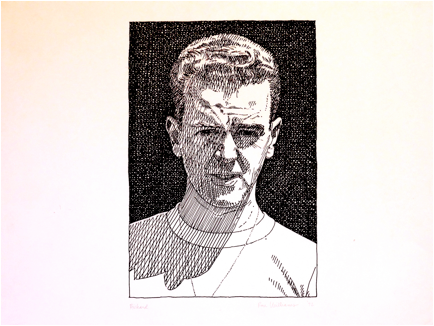

Sometime later another drawing was noticed, this one a portrait, to also be out of kilter with the paper's edges. It too was traced and the image was almost imperceptibly wider at the bottom than at the top. It also occasionally presented itself as three dimensional, an illusion invited study so as to determine where the effect had come from. Eventually, it was realized that perspective had shown up unexpectedly, in an unexpected place: it was the frame that was in perspective and stood in front of the subject, diminishing the flatness of the surface it was drawn on.

Dick

"The art of painting is an art of thinking, whose existence underlines the importance of the role held in life by the eyes of the human body”, Rene Magritte

Analogue drawing, done digitally.

Some copies of the early ONYX posters still exist in good condition. These and reproductions of other prints like the colored broadsheets and many of Ron's images are available. Go to the ONYX Gallery to see available ONYX works.